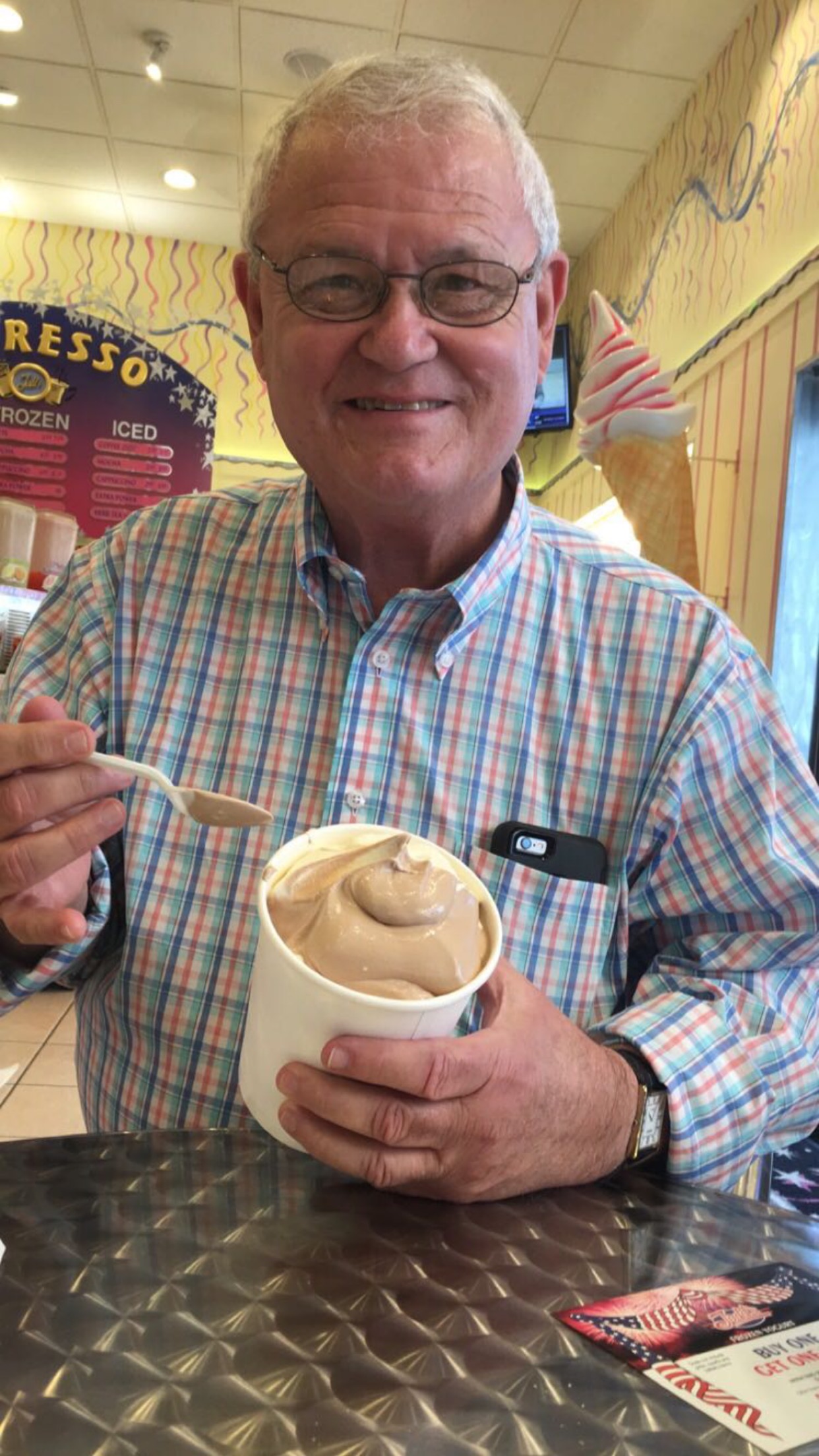

Ed Muniz, who built Endymion into superkrewe, served as Kenner mayor, dies at 83

Gentilly product made millions in radio, served 27 years in Jefferson Parish politics

Ed Muniz once said he’d done three things in his life: politics, radio and Mardi Gras.

He did none of them halfway.

Muniz, who died Saturday at 83 after several years of declining health and dementia, worked his way up in the radio business to owning, then selling, multiple stations. His 28 years in Jefferson Parish politics included stints on the Kenner City Council and the Jefferson Parish Council and as Kenner’s mayor.

Muniz, who died Saturday at 83 after several years of declining health and dementia, worked his way up in the radio business to owning, then selling, multiple stations. His 28 years in Jefferson Parish politics included stints on the Kenner City Council and the Jefferson Parish Council and as Kenner’s mayor.

He eventually got out of radio and politics, but not Carnival. Arguably his most enduring public legacy is Endymion, the little krewe he founded in 1966 in New Orleans’ Gentilly area and then led through more than half a century of growth.

“The transformation of Endymion from an ordinary neighborhood parade into an extraordinary super-parade is the result of pure genius, the genius of one Edmond Muniz,” Arthur Hardy, the Mardi Gras Guide publisher, wrote in 2016, the year Endymion celebrated its 50th anniversary. “It would not be an exaggeration to declare him one of the most significant figures in the history of Mardi Gras.”

Humble beginnings

Muniz grew up in Gentilly not far from the Fair Grounds. As a kid, he was a self-described “parade nut,” testing his parents’ endurance. His grandfather worked at Gallier Hall and got him tickets to its parade viewing stand.

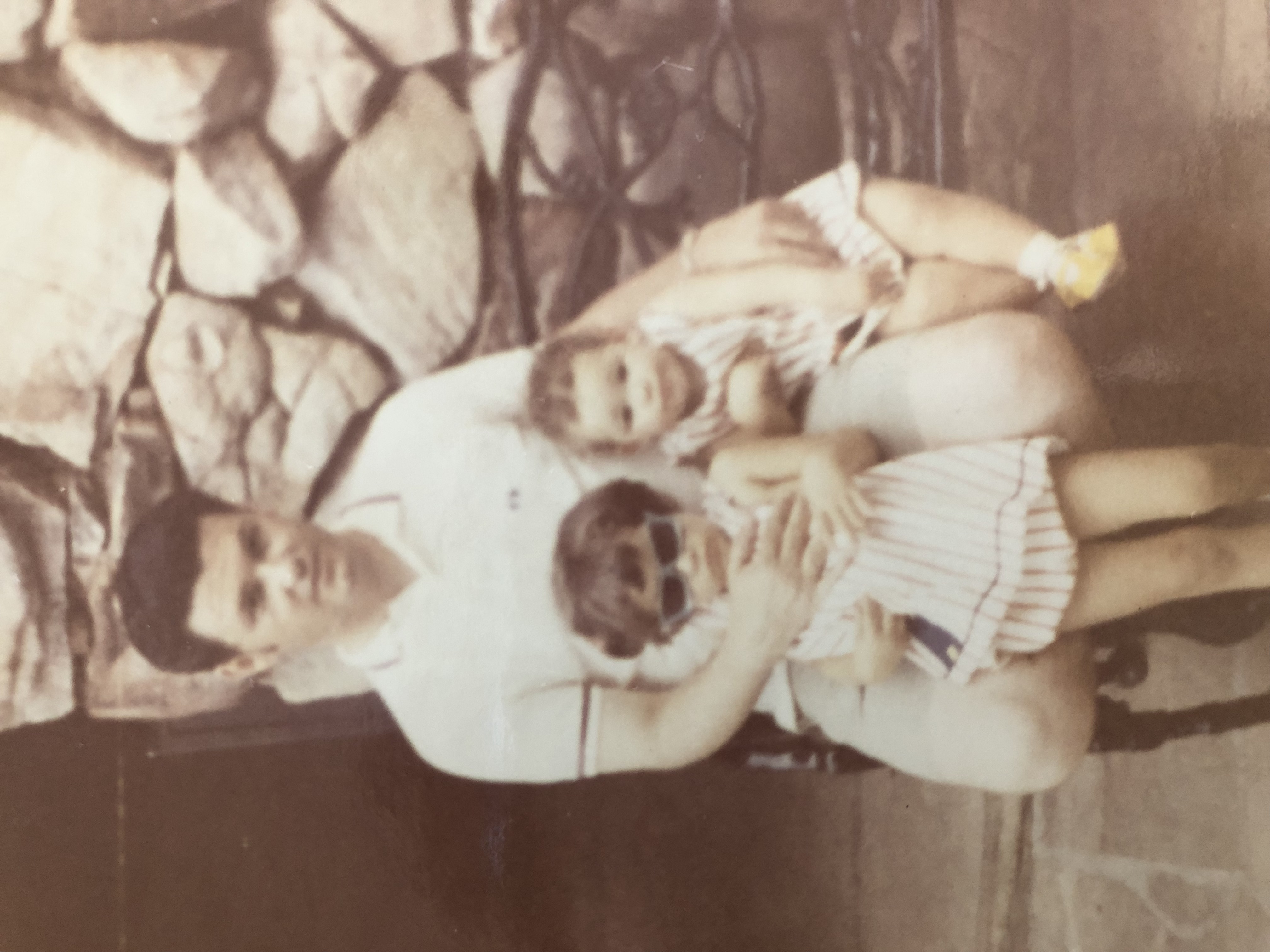

After graduating from St. Aloysius High School, Muniz paid $45 to ride in the Krewe of Thoth. Marriage changed things, especially when he and his wife, Peggy, welcomed their first daughter “10 months and two days after we got married,” Muniz recalled in 2016. “I couldn’t afford to be in Carnival.”

He still attended parades regularly. After the demise of the Krewe of Adonis left a void downtown on the Saturday night before Fat Tuesday, Muniz resolved to fill it, despite his utter lack of old-line Carnival pedigree.

He still attended parades regularly. After the demise of the Krewe of Adonis left a void downtown on the Saturday night before Fat Tuesday, Muniz resolved to fill it, despite his utter lack of old-line Carnival pedigree.

“I wasn’t well known or a big shot,” he said. “I didn’t come from a Garden District family. I came from the Fair Grounds. Peggy came from Chalmette.”

Back then, various neighborhoods still hosted parades, including the Krewe of Carrollton. Muniz “wanted to be the Carrollton of Gentilly. That was my ambition.”

Carrollton’s captain, John Ackermann, rented 16 floats to Muniz for $5,000. Muniz incorporated his nonprofit group as the Gentilly Carnival Club. Mayor Victor Schiro gave him a permit for a parade that would start near the Fair Grounds, at Trafalgar Street and DeSaix Boulevard.

In need of a name, Muniz flipped through a library book about mythology. A description of Endymion, the Greek god of eternal youth and fertility, caught his eye, in part because he had won a $2 bet on a horse named Endymion.

Endymion the god “was fertile: He had 50 daughters and four sons,” Muniz said. “He was the most handsome of all the gods. I wanted it to be a young krewe, so what could be any better than this guy?”

One problem: “People couldn’t pronounce it, other than the ones (who) went to the racetrack, because they knew the horse.”

The first, modest Endymion parade rolled Feb. 4, 1967, with the theme “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” The 150 or so members were mostly from the neighborhood.

The first, modest Endymion parade rolled Feb. 4, 1967, with the theme “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” The 150 or so members were mostly from the neighborhood.

Within a few years, Endymion had more riders than the 16 rented Carrollton floats could accommodate. Muniz leased more from float designer and builder Blaine Kern. Some years, the budget was lean. “There were times we would roll on bad tires, because we didn’t have the money” to replace them, Muniz said. “That bit us on the ass a few times.”

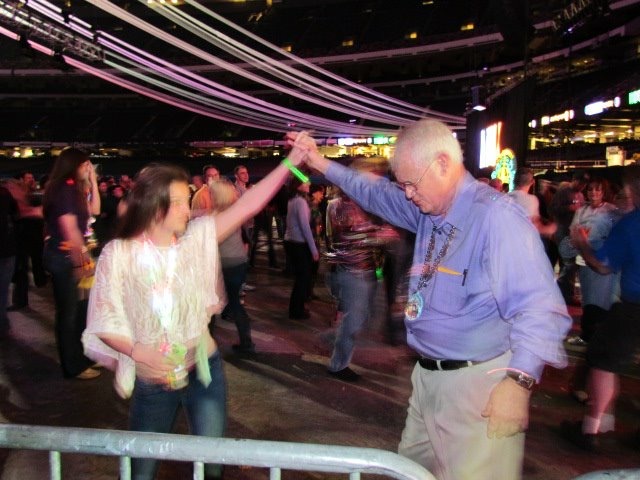

After attending the 1973 Bacchus Rendezvous, featuring celebrity monarch Bob Hope, Muniz was inspired. The next year, he hired Doc Severinsen, famed leader of “The Tonight Show” band, to headline the post-parade Endymion Extravaganza. The Extravaganza eventually evolved into a mass tailgate party in formal wear for 20,000 revelers in the Superdome.

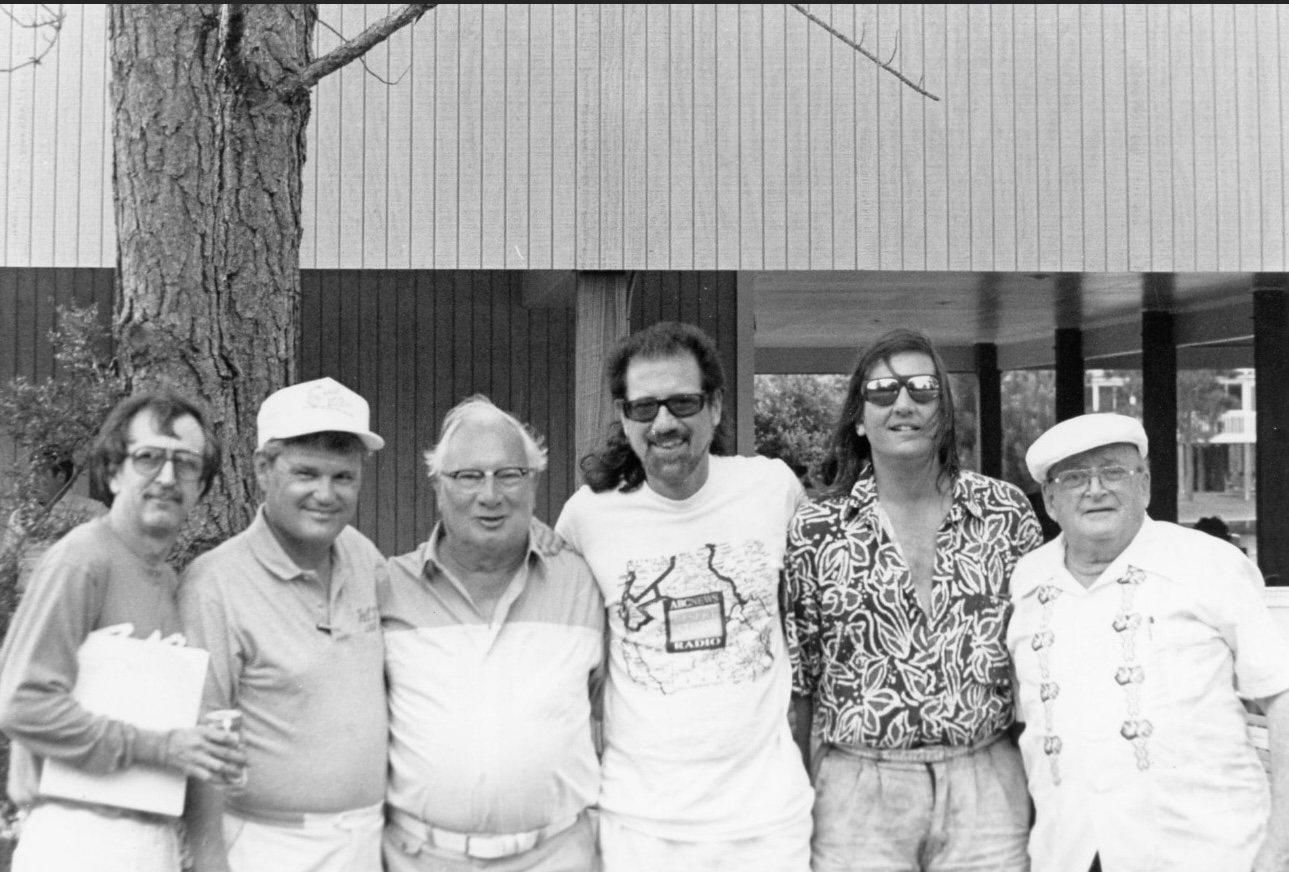

The parade grew throughout the 1970s with the support of everyone from rocker Alice Cooper, Endymion’s 1976 grand marshal, to famed WWL-TV sportscaster Hap Glaudi.

When crowds overwhelmed Endymion’s original route, the parade moved to a new starting point on Orleans Avenue in Mid-City. To generate excitement, the krewe staged a “Samedi Gras” pre-parade festival on the neutral ground, a tradition that endures.

With more than 3,000 riders aboard elaborately designed and lighted floats, Endymion is now one of Carnival’s biggest and brashest parades, an hours-long procession of marching bands and elaborate, multi-unit floats with an annual operating budget in the millions of dollars.

The only major New Orleans parade not to follow the now-standard Uptown route, Endymion still reflects Muniz’s guiding philosophy of fun over formality.

A move to Kenner, a radio empire

In 1975, Muniz and his expanding family were still squeezed into a two-bedroom home on DeSaix Boulevard. One day, he and Peggy, to whom he was married for 58 years, took a break from their hospital vigil for Muniz’s terminally ill father. On a whim, they followed Parade of Homes signs to a new subdivision in Kenner, Chateau Estates.

They liked what they saw and bought a house. Within a few years, they purchased a nearby house from a member of Endymion.

As good as he was at building a parade, Muniz was equally adept at building revenue for radio stations. He progressed from selling advertising to owning small-market stations across the Gulf Coast.

He eventually grew weary of commuting, so he and his partners sold their stations. Muniz kept two New Orleans powerhouse: WLTS-FM Lite 105 and WTKL-FM Kool 95.7. After initially turning down lucrative offers from national media companies, Muniz finally cashed out in 2000, reportedly to the tune of millions of dollars.

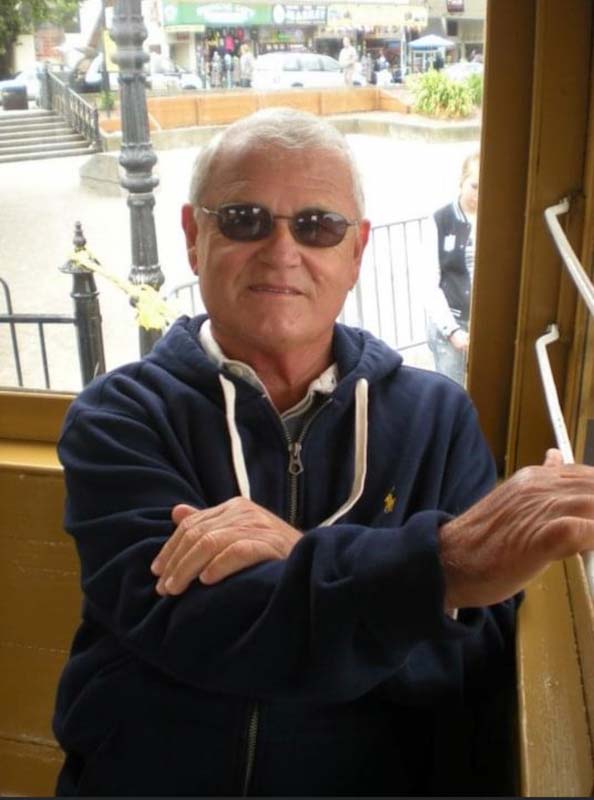

His frugal lifestyle didn’t change, however. He still favored jeans, sneakers, flannel shirts and the Kenner house he bought long ago.

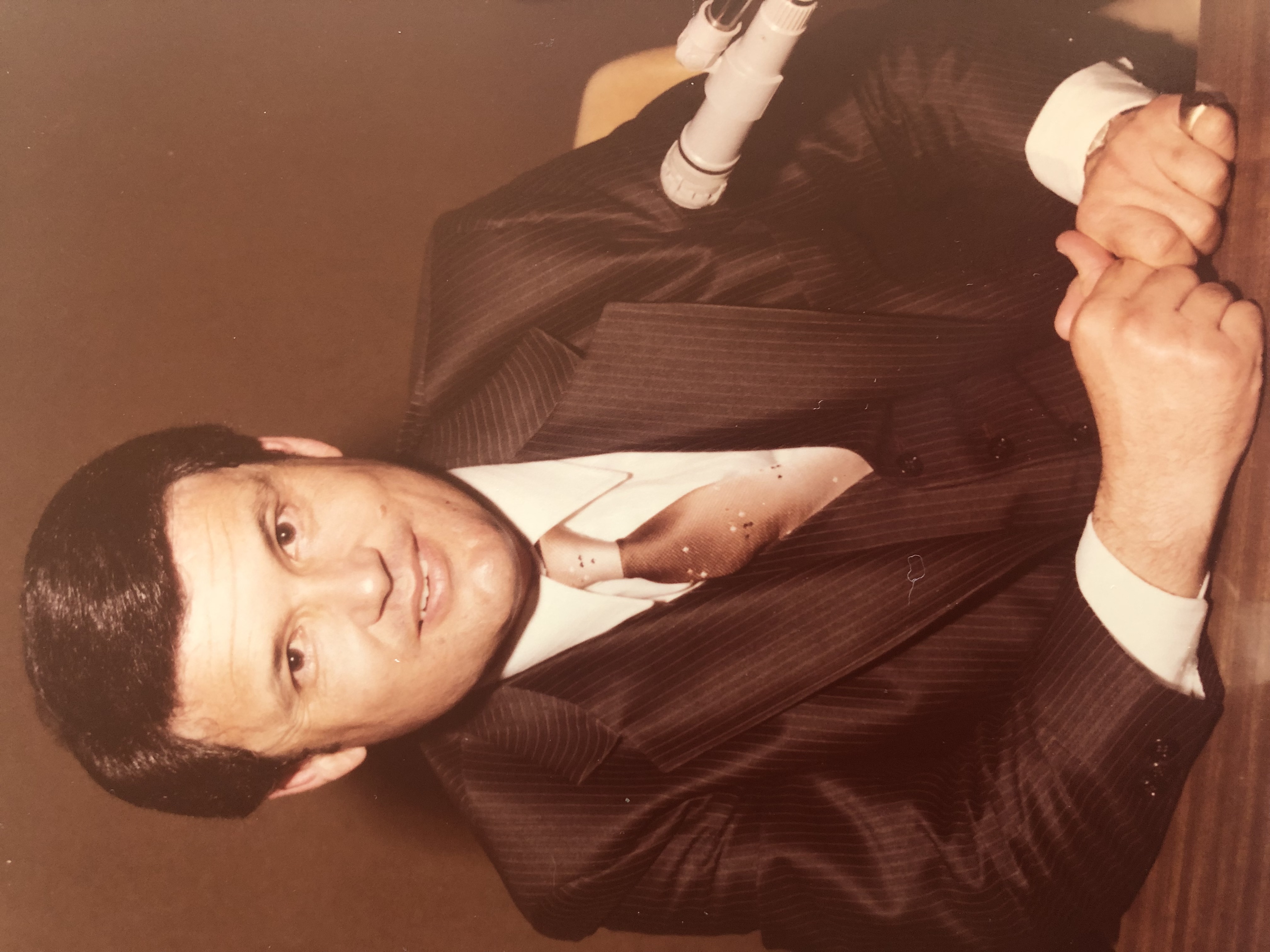

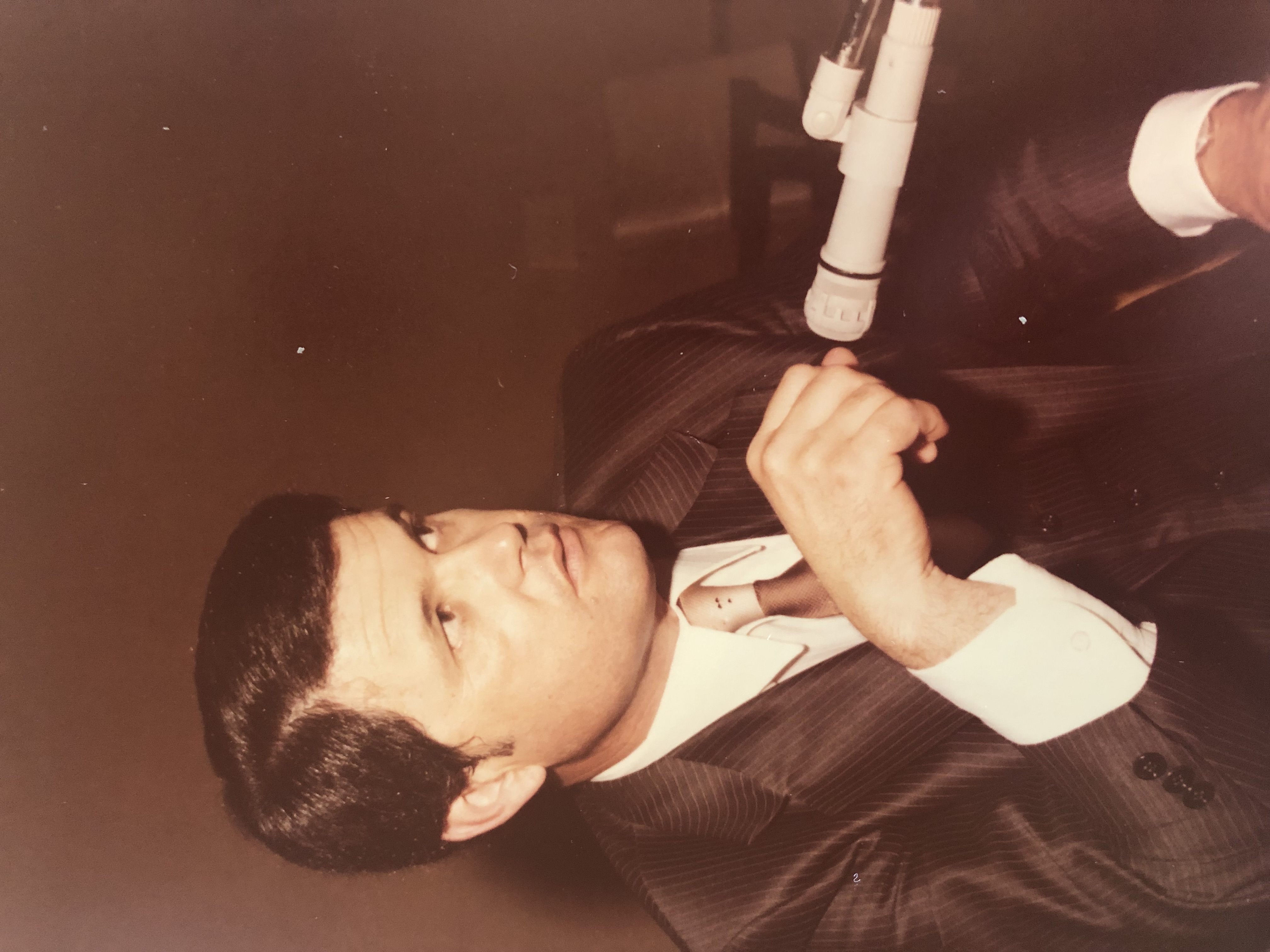

A political side career

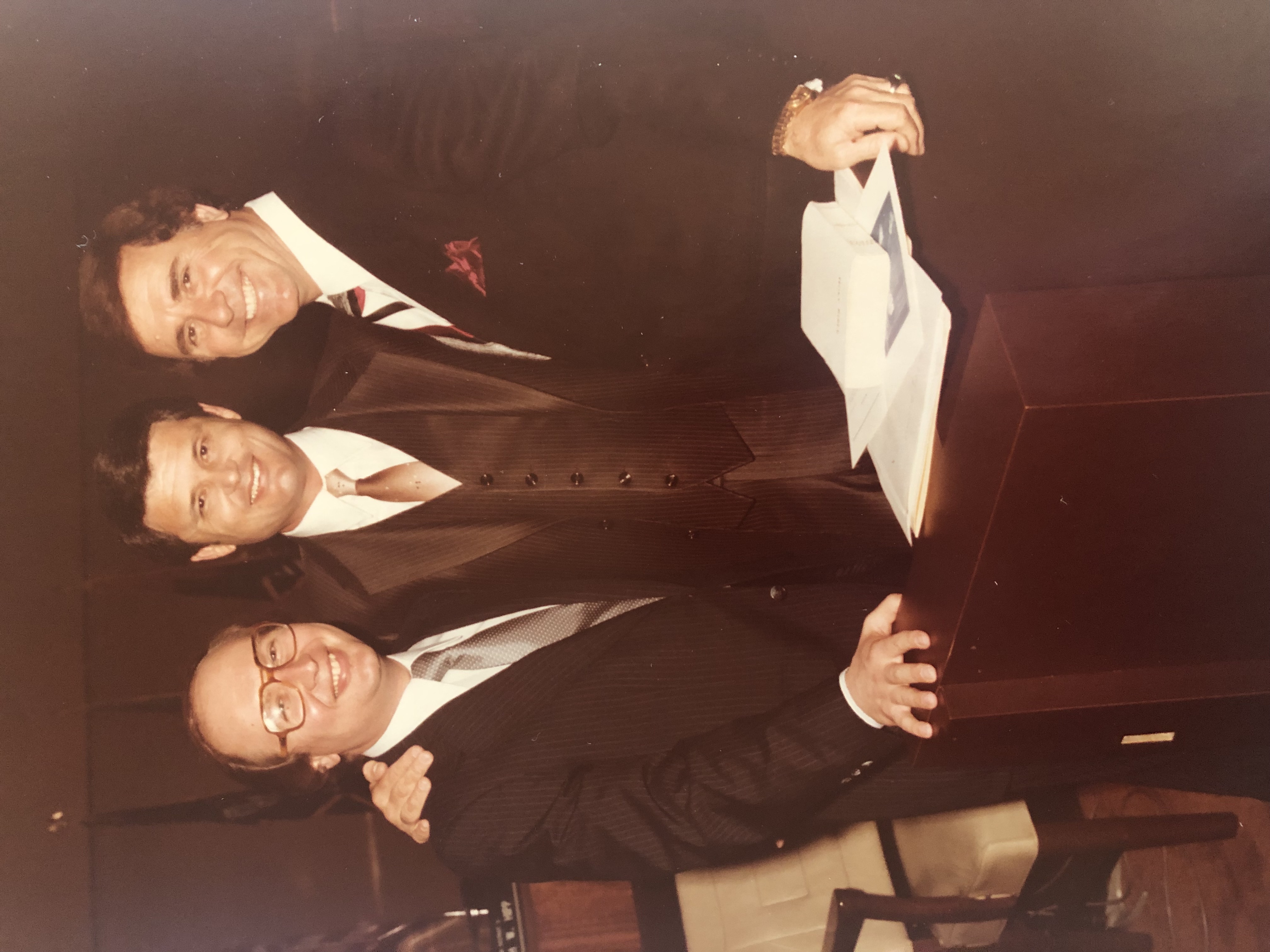

Muniz launched a side career in Jefferson Parish politics in 1980, which turned out to span seven years on the Kenner City Council, followed by 17 more on the Jefferson Parish Council. He lost a race for an at-large Parish Council seat in 2003, but he didn’t dwell on it.

Muniz launched a side career in Jefferson Parish politics in 1980, which turned out to span seven years on the Kenner City Council, followed by 17 more on the Jefferson Parish Council. He lost a race for an at-large Parish Council seat in 2003, but he didn’t dwell on it.

“We lost one election, but we won seven elections,” he said at the time. “I owned radio stations. On a whim, I started a little b.s. Carnival club, and now it’s one of the biggest around. The good Lord has blessed me.”

In 2006, he came out of retirement to defeat Kenner mayor Phil Capitano in a runoff. More than once, he heard, “We voted for you because we love your parade.”

On the Parish Council, he pressed his colleagues to select architects, engineers and lawyers in public instead of in back rooms. He crusaded to ban shell dredging in Lake Pontchartrain. He tried to bar council members from awarding contracts to fat-cat campaign contributors, and to make the contributors disclose donations. He pushed the council to seek competitive bids, instead of fuzzier “proposals,” for its lucrative garbage collection contract.

“Mayor Muniz was known for his transparent and fiscally conservative values, where during his time in public office he prioritized conducting government business in public and supported maintaining quality services at a cost savings,” Kenner Mayor Mike Glaser said Saturday. “He supported strict adherence to zoning laws, the preservation of residential neighborhoods, a cleaner environment, the protection of Lake Pontchartrain, and the economic well being of local businesses.”

Though not one to dominate the microphone at public meetings, Muniz could talk for hours one on one. Gregarious, entertaining and an inveterate rambler, he could shift from politics to the Bible to Carnival to personal memories without taking a breath, segueing at just the right moment with “the point I’m making is” or “to make a long story short.”

Invariably, the story was both long and entertaining.

Parade a family affair

Frustrated at Kenner City Hall by executive branch limitations and aggravations, Muniz declined to seek a second term as mayor, which gave him more time to be mayor of Endymion.

Frustrated at Kenner City Hall by executive branch limitations and aggravations, Muniz declined to seek a second term as mayor, which gave him more time to be mayor of Endymion.

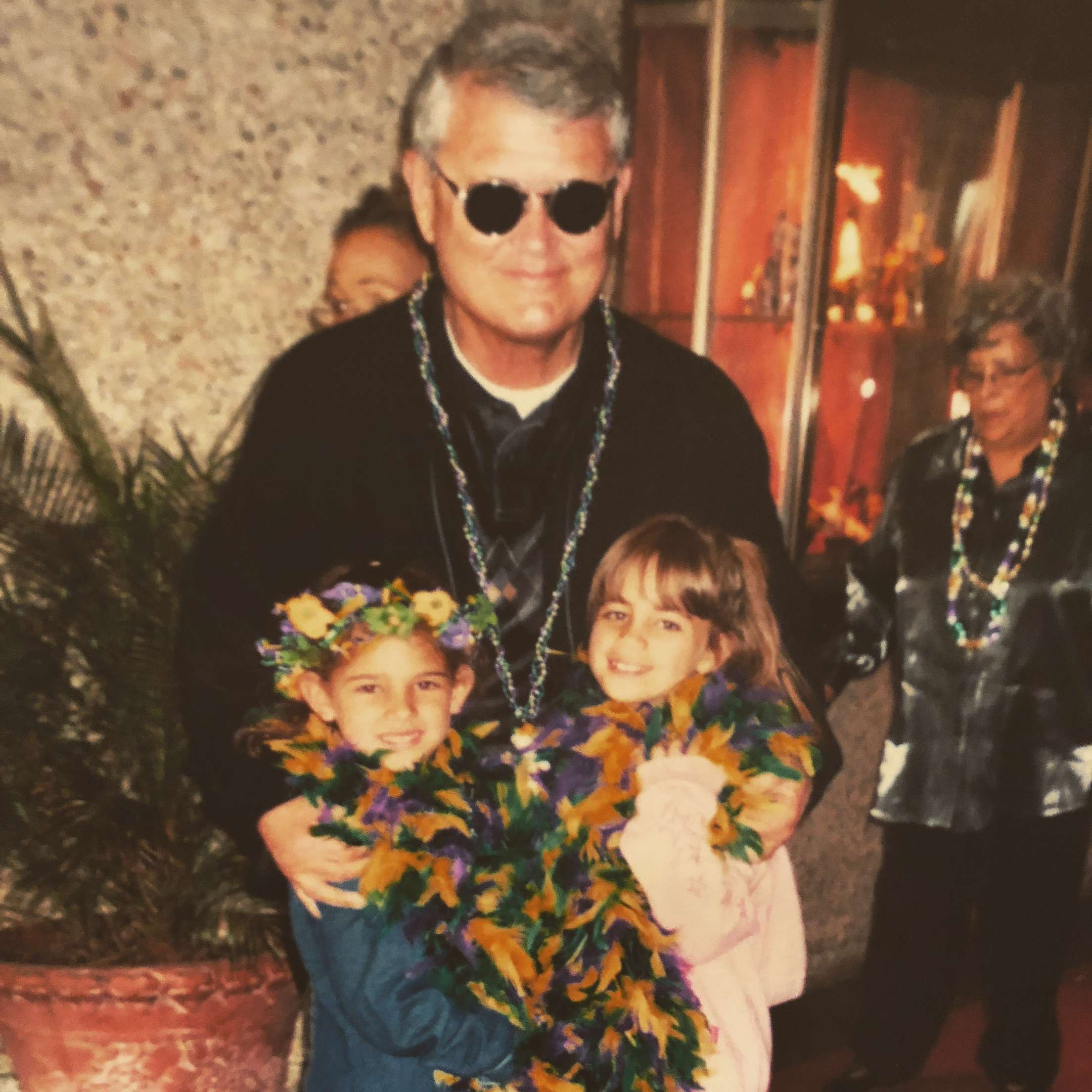

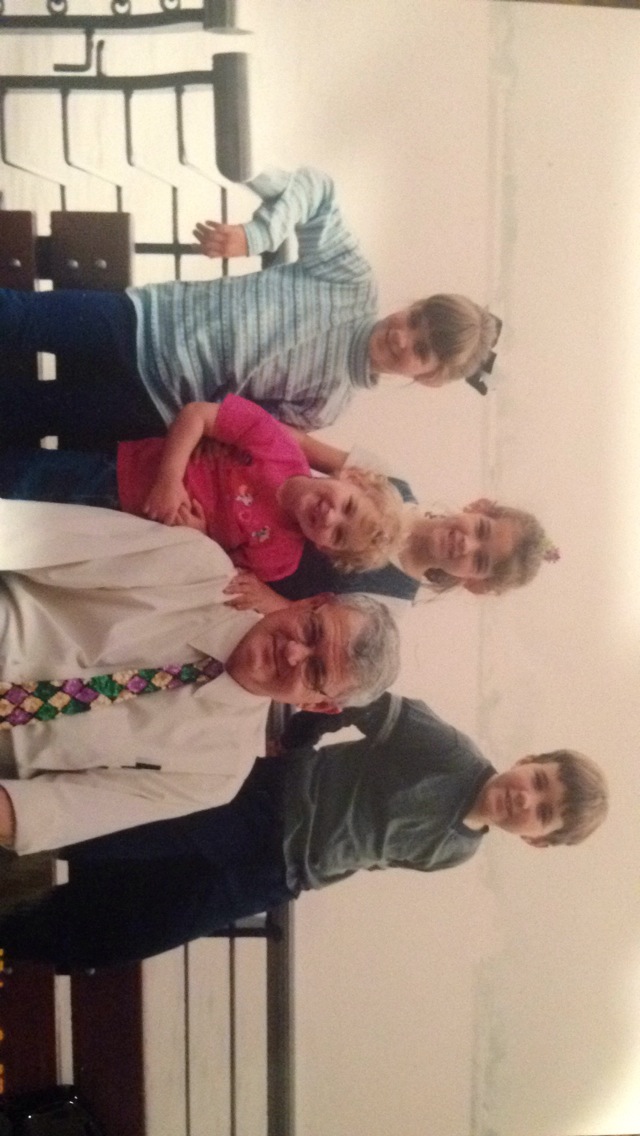

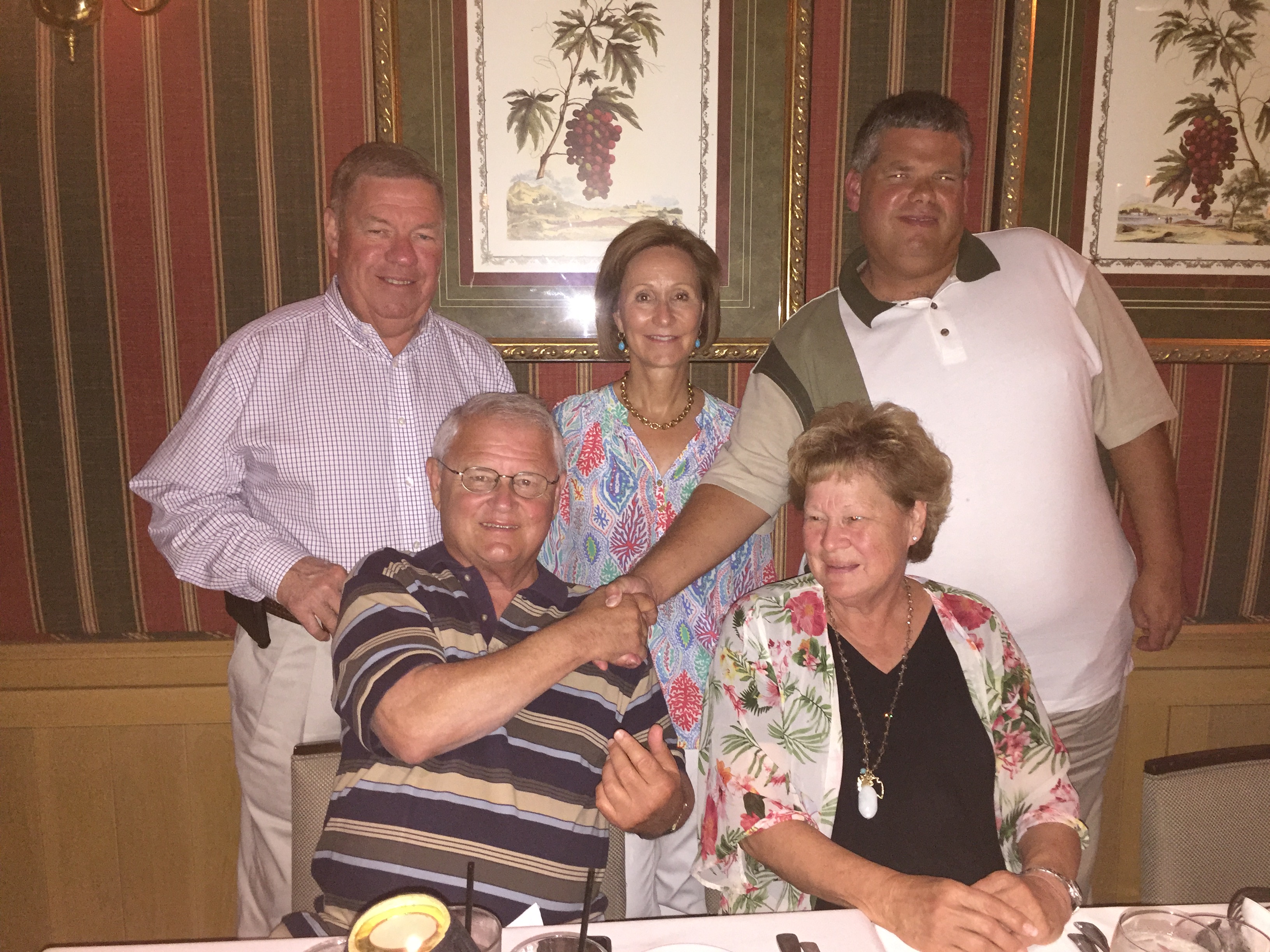

At its core, Endymion was a family affair. Muniz’s three daughters served as queen, as did his granddaughters. His son-in-law, Darryl d’Aquin, is the organization’s vice president.

Dinner table discussions sometimes involved potential parade themes and entertainers. The riverboat-themed “Poppa Joe’s S.S. Endymion” float is named for Muniz’s father, who died three days before the float made its debut in 1976.

In 2020, Ed Muniz himself was the subject of an Endymion float. That turned out to be the final year he rode at the front of the parade as its masked captain.

A week before his death, the Endymion Garden opened on the Delgado Community College campus, steps from where the parade lines up along Marconi Drive at Orleans Avenue. The garden features a 7-foot statue of Muniz, crafted by Kern Studios, walking hand-in-hand with the Endymion cartoon mascot.

Survivors include his wife, Peggy; three daughters, Mary Muniz d’Aquin, Michelle Muniz Hanzo and Margie Muniz Bateman; four grandchildren; and one great-grandchild. Funeral arrangements were incomplete.

Article by: Keith Spera, with Drew Broach contributing